Nelson George is a force. There’s really no other way to describe him. Author, columnist, filmmaker, music cultural critic, and journalist are just a handful of the credits attributable to his long and distinguished career. He’s written and/or produced and/or directed numerous short films, feature films and documentaries for both the big and small screens and has written several books and countless articles. He’s been nominated twice for the National Book Critics Circle Award, received a NAACP Image Award in 2012 for Outstanding Literary Work and a Sports Emmy Award in 2013 for Outstanding Sports Documentary. I could go on, but you get where I’m going. . . . A creative powerhouse.

My original entrée into “The World According to Nelson” was through his 2012 documentary, Brooklyn Boheme. Co-directed by Diane Paragas, Brooklyn Boheme explores the rich and uniquely diverse African-American and Latino artistic explosion that took place in the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill neighborhoods of Brooklyn during the 80’s and 90’s. Featuring Spike Lee, Rosie Perez, Branford Marsalis, Erykah Badu, Chris Rock, and Saul Williams – just to name a few – the documentary endearingly chronicles the rise of a new type of artist of color very much akin to the great poets, painters and playwrights born of the Harlem Renaissance. George has lived in Fort Greene much of his adult life and in 1986 helped finance Spike Lee’s film, She’s Gotta Have It, shot locally. There’s no question George loves his ‘hood, and Brooklyn Boheme feels like a ballad, an ode to a place very near and dear to his heart.

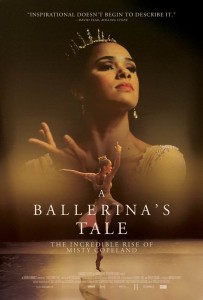

In his latest work, a documentary feature film entitled A Ballerina’s Tale which had its premiere at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival, George follows the inspiring story of African-American ballerina Misty Copeland, a (now) principal ballerina with the American Ballet Theatre (ABT). You may recall hearing this past summer about the dancer’s rise from soloist with the ABT to principal, making her the first black principal ballerina of a major international ballet company. George’s film precedes this ascendancy by several years finding Copeland in the middle of her professional career and fighting her way back from a debilitating stress fracture. And while the story of Copeland’s near career-ending injury is a main anchor of the film, the real focus (and presumably its raison d’être) serves to highlight, among other things, the lack of diversity in the world of ballet, a world described in the film as possibly “one of the last bastions of [permissive] racism.” Where the long idealized visual aesthetic, first introduced by choreographer George Balanchine considered by most to be the father of American ballet, is tied to a certain body image and where assimilation and uniformity are the preferred norm.

Through Copeland’s story, George’s documentary also manages to lift up the names of some of the black ballerinas who blazed their own trails long before Copeland arrived on the scene. Such notable dancers include Raven Wilkinson, the first black ballerina ever to be employed by an American touring company. She was hired by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1956 and retired from the company in 1960. Also featured is Victoria Rowell, an actor (who you may recognize from the daytime soap opera, The Young and Restless, on which she played the recurring role of Drucilla Williams for many years before leaving the show) and dancer who was a member of the ABT Studio Company from 1979 – 1983.

In detailing her own story, Copeland talks at length about the challenges she faced early in her ABT career particularly as related to race and body image. She describes an instance one evening after rehearsal, in the midst of a low self-esteem spiral, when she ordered, had delivered and then consumed a dozen Krispy Kreme donuts in one sitting. She was struggling because she was the only black dancer in a company of 80. She was struggling because she didn’t know how to process a request that she lose weight, something she’d never been asked to do before. She speaks of herself as a muscular black woman with a large chest. A body type the company felt needed addressing.

And the film is full of moments where Copeland wears her emotions entirely on her sleeve, where you have an intrinsic understanding of what she must be feeling. Her frustrations, disappointments, her fear. But also her joy. In the end, her infectious joy. She is electric both onstage and off. A prima ballerina with a grace and technique that is unparalleled, and a smile that could launch a thousand ships.

George spent many years trying to get this film made. Thanks to a 2014 Tribeca Film Institute Documentary Fund award, a Kickstarter campaign that raised about $54,000 and support from American Express, his film is finally a reality. You can see it now at Landmark Cinemas nationwide as well as on Amazon, iTunes and On Demand.