To describe the immigrant journey to a distant border as oft times emotionally treacherous and physically challenging doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of the thing. Particularly if immigrants are fleeing war, poverty, or persecution to find refuge in more hospitable environs. Yes, we’ve all seen countless images of people crammed into small dinghies somewhere in the middle of an ocean, precariously spilling over the sides trying desperately to make it to land. But, in truth, most of us have absolutely no idea what those harrowing journeys entail. We think we may have some sense of it, but deep inside we know enough to know that we couldn’t possibly have any idea. Not really.

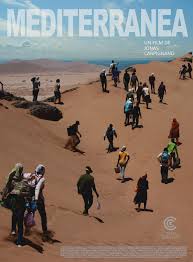

It is this “middle passage,” this journey separating an immigrant’s past from his future, and the experiences that follow that give shape and form to Mediterranea, the first feature-length film from director Jonas Carpignano. Carpignano was born in New York to an Italian father and an African-American mother and raised partly in Rome. Mediterranea expands on Carpignano’s short film, A Chjana, which won the Best Short Film Award at the 2011 Venice Film Festival. A Chjana dramatized real events that occurred in the Calabria region of Italy in 2010 where the worst race riots in Italian history broke out in the town of Rosarno. The rioting began after a legal immigrant from Togo was wounded in a pellet-gun attack in a nearby town. Citing racism for the attack, dozens of immigrants burned cars and smashed storefront windows during two days of rioting. More than 50 immigrants and police officers were hurt, and several immigrants and locals were arrested before more than a thousand African day laborers were put aboard buses and trains and shipped to immigrant detention centers in other parts of southern Italy. And in the days following the riots, Rosarno authorities bulldozed the makeshift encampments just outside the town where hundreds of African immigrants had been living in what was described by some as “subhuman conditions.”

Carpignano originally went to the Calabria region to shoot his short film and ended up staying for five years. During casting, Carpignano met Koudous Seihon, an African of Ghanaian-Burkinabe descent who’d been active in the defense of the immigrant workers involved in the Rosarno riots. Inspired by Seihon’s activism, Carpignano felt called to tell a more in-depth story of the African immigrant experience in Italy, and the feature was born. Seihon plays the film’s main character, Ayiva.

In the opening scenes of Mediterranea, Ayiva and his friend, Abas, and others are preparing to board the back of a truck leaving Burkina Faso and headed for Algeria. Once there the two men join a group that has decided to risk traveling on foot through the North African desert in order to reach Tripoli, Libya where a boat will then transport them to Italy. During their crossing they are ambushed by a group of bandits who loot and terrorize them, leaving one immigrant for dead.

We next see Ayiva and Abas walking the streets of Tripoli making plans for the Italian leg of their journey. When the time comes for they and the other immigrants to board a small dinghy, looking no more sturdy than an inflatable raft, they are told by the owner of the boat, presumably the person responsible for securing their safe passage, that he will not be helping them across the Mediterranean Sea as promised. Instead, he says, one of the immigrants must captain the boat. Ayiva agrees to steer the ship, and they set off on their voyage. But stormy weather rolls in soon after their departure, and they are shipwrecked only to be picked up by the Italian Coast Guard. Ayiva and Abas are held in an immigrant detention center and then released on a three month visa. They take up residence in a makeshift shantytown and begin the arduous task of finding paid work in Italy. The work they ultimately settle on – as day laborers picking oranges in a citrus grove – is the primary means of employment for many of the African immigrants and a source of consternation for some of the townspeople. Soon tensions flare between the immigrants and the locals ultimately leading to rioting in the streets one night after two blacks are killed by police. The protestors march through town chanting, “Stop Shooting Blacks, Stop Shooting Blacks,” and Ayiva and Abas are leading the charge.

The events that follow in the film feel real, not fictionalized. They feel as if they’ve been ripped from today’s national headlines and transplanted a continent away. Almost as if the protestors could have been holding up “Black Lives Matter” signs while they marched and chanted, and no one would have batted an eye. In this way Mediterranea is both relevant and timely but with a twist. It’s about the lives of black people, yes, but lives we rarely see. The lives of black immigrants, far from home and completely vulnerable. Lives lived in the shadows but yearning to be seen. And through its making the film does just that, it shines a light into the darkness and makes the unknown known.

In the end, though, this film is really just a story about Ayiva and his choices. His choice to leave his home, sister and seven-year-old daughter behind; his choice to endure the hardship and monotony of work as a day laborer so that he can send money back to his family; and his ultimate choice to remain in Italy when he’s clearly aware of the hard road that lies ahead. He stays. He chooses the light, the opening, the possibility of better. Presumably because he wants for himself and his family what we all want – a life of hope and promise and recognition. In the end, a life that matters.